The History of Trademarks

Abstract:

The history of trademarks, which have become one of the crucial components of trade affairs, is explained in this study. This study contends that the modern trademarks did not just pop up abruptly but were affected, in one way or another, by the signs, signatures, etc., that were used in the past and that it is these historical marks and signs that had paved the way for the modern trademarks and their current situation.

A - Introduction:

The desire of human beings to mark articles started at the very first times of their existence.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lascaux_painting.jpg

----------

In scholarly literature, it was argued that trademarks had been used for centuries, probably as long as there has been more than one person carrying out a particular trade, or selling merchandise of a specific type, at the same market or in the same town. (Shilling, 2002: 1-1) Another argument was that the trademarks could be seen and dated back around 5,000 years B.C. to the Bison-painted walls of the Lascaux Caves in southern France. (Johnson, 2005) In addition to the stated assertions, some scholars indicated that these ancient marks were presumably used to identify ownership rather than to serve some business function and, thus, the history of trademarks dated back to Mesopotamian and Egyptian Civilization. (Foster, F.H. – Shook, R.L.: 19 – 23) Some others allege that the signs of an ancient civilization were property marks and, for that reason, the ancestors of modern trademarks, firstly traced back to the twelfth century. (Tekinalp: 303)

B – History of Trademarks:

Compared to its long history, it is a relatively recent development that the trademark has become a component worthy of legal protection by being included in the property right. However, it is indisputable that the evolution and history of the trademark paved the way for its current definition, classification, and consequences.

The following section will explain the evolution of the trademark and its types by dividing them into different periods from the beginning.

I) Trademark in Ancient Era:

Mud Brick Stamped with the Royal Names of Aakheperkare

(Thutmose I) and Maatkare (Hatshepsut)

Source: Official website of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (The MET) https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/560619

----------

The first traces of trademark were observed between 3500 and 3200 B.C. in Mesopotamia and Egypt, specifically on bricks, roof tiles (brick marks), and building sites. The concerned signs were composed of the factory and the makers’ names (sometimes, additional information such as the name of the consul or emperor, building contractor, etc.) and stamped to the appropriate places of the articles. Although it is hard to allege that these signs bear the stamp and features of a modern trademark, they had the most crucial feature of a trademark: distinctiveness. Nevertheless, the reason behind the usage of those signs was a bit different: Quarry marks indicated the source of the stones used in buildings, and stonecutters’ signs, which might be either painted on or carved into the stone, helped workers prove their claims to wages. (Winterfeldt, B.J.) II)

II - Trademark in the Roman Era:

Source: http://www.frisius-f.de/index_en.html

----------

The Roman civilization, which existed between 500 BC and 500 AD, provides the earliest documented record of an economy that used trademarks on a daily basis. (Foster-Shook: 20)

The Romans used markings not only on their nourishment (cheese, wine, bread, etc.) but also on their bricks, tiles, building stones, pottery, amphorae, etc. The pottery marks were perhaps the most dominant type seen in Roman civilization. It is claimed that an estimated 6,000 different Roman potter’s marks have been identified, some of them quite clever and surprisingly on par with today’s trademarks (Foster-Shook: 20).

Originally, marks of those times consisted of a single line of letters framed by an oblong with rounded or swallow-tailed corners. Later, one more line was added, and the shape changed to a circle, semi-circle, or crescent. The signatures were accompanied by an F (Fecit), O, OF (Officina), or M (Manu). (Rudofsky: 6)

III) Trademark in Dark Ages:

It is a common approach that early medieval Europe, referred to as the “dark” age, managed to break through a number of technological barriers that had held the civilizations back. (Mokyr: 31)

The period between the fall of the Roman Empire (fifth century) through the thirteenth century is regarded as the era of illiteracy or the dark ages for trademarks, as there is no adequate evidence that trademarks continued to be used in everyday life.

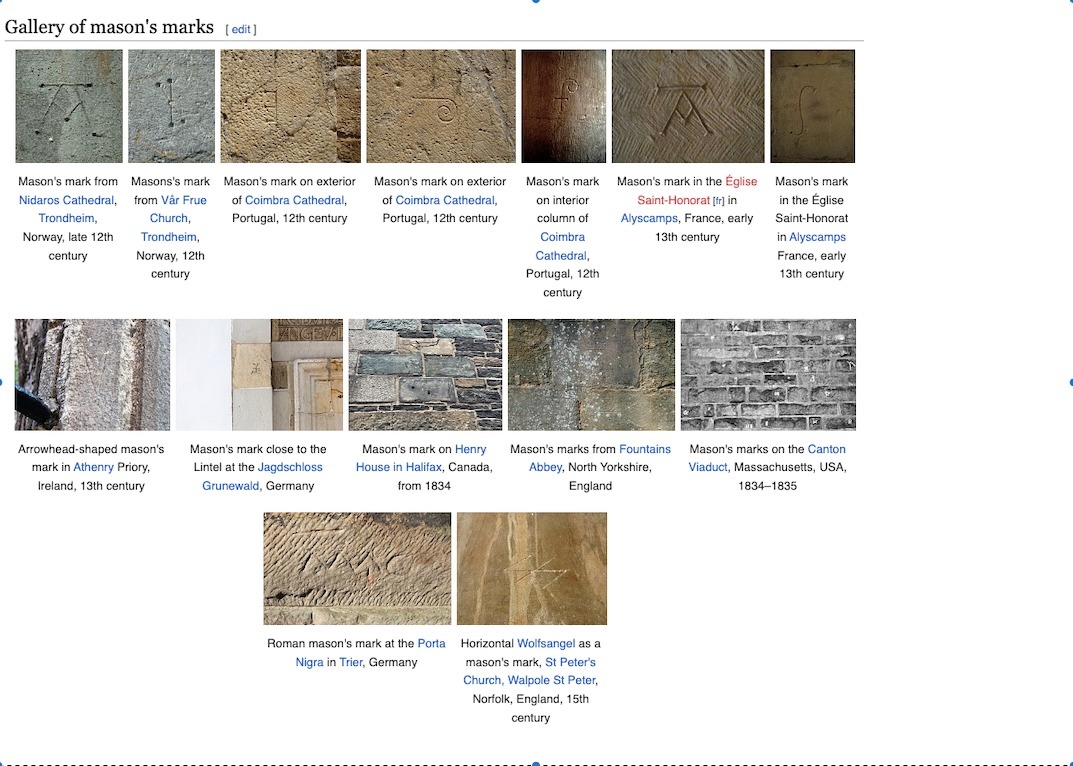

During this period, medieval stonemason marks were used.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mason%27s_mark

----------

The masons developed a different way of communication, that is to say, a complicated ritual of speech and behavior. Because of the mentioned approach and conception, trademark types have changed. In this period, neither numeric nor alphabetical characters were used, and symbols or inscriptions that could only be understood by a member of a guild were preferred instead.

IV) Printer’s Marks, Merchant’s (Police) Marks:

While signs were used by almost every merchant or craftsman (bakers, bottle makers, blacksmiths, armorers, metalworkers, wool and linen weavers, etc.) after the Dark Ages, the most important were those of printers and merchants.

One of the most well-known old printer's marks is the dolphin and anchor, first used by the Venetian printer Aldus Manutius as his mark in 1502. (Nicole Howard (2005), "Printer's Devices", The book: the life story of a technology, Bloomsbury Academic, ISBN 9780313330285)

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Printer%27s_mark

----------

It was only after the invention of book printing that the mass production of books became possible. This development paved the way for printers to use a sign or mark to distinguish their goods (i.e.: books) from other printers.

Psalterium Latinum, printed in Mayence by Johann Fust and Peter Schöffer, was the first book to be printed under the printing press stamp. It was also the first book to bear the printing date of August 14, 1457. (Rudofsky: 21)

The use of guild and merchant marks coincided with the use of printing marks. One could argue that the guarantee function of a trademark may have been acquired from guild brands.

Up until the French Revolution, merchants in Europe were not allowed to advertise, and their transactions were controlled by the guilds. Each guild had the right to set its own regulatory rules, and as members of these guilds, merchants had to use the guild’s marks on every product they produced. Due to the mandatory nature of these marks, they were also considered police marks. The guilt regulations required that every product produced by one of its members bear both the guild symbol and the mark of the individual artisan. The guild’s mark let the public know that the goods were not contraband. However, it also held the artisan responsible for poor workmanship, and disciplinary action was taken for failure to comply with guild standards. (Foster-Shook: 21)

The French Revolution (1789) abolished all privileges granted to the guilds and, thus the dominance of the guilds and the obligation to use signs herein ended. Despite these developments, signs continued to be used as people realized that these signs provided them with many advantages.

C — Modern Trademarks:

The need to protect the component (the trademark) that distinguishes, identifies, promotes, and guarantees these products has increased as business transactions and firms have grown and become multinational in nature.

Several international and national legislations have been enacted starting from the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property(1883). After these national and international agreements, laws, decrees, etc., trademarks have gained their current status.

The following section will briefly explain ‘right,’ ‘intellectual property right,’ and ‘trademarks and their place within the concept of intellectual property’ to determine the current position of the trademark.

C.1. The Concept and Types of “Rights” and “Intellectual Property Rights”:

The right is legally defined as follows: “The authority granted to real or legal persons by the legal system.” (Kılıçoğlu, 2002: 12)

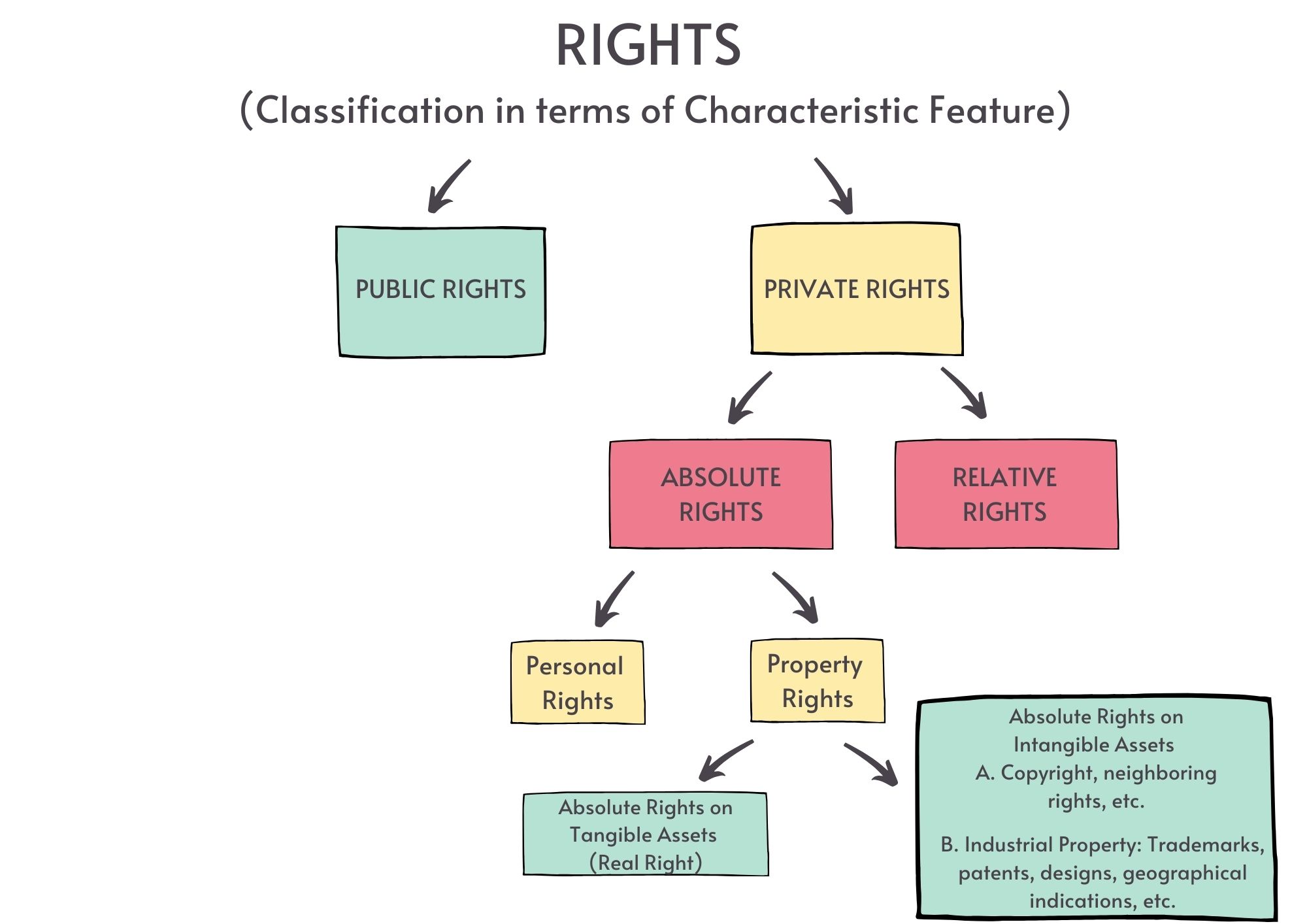

In the scholarly literature, although it is observed that rights are classified in different ways (for example, see Öztan, 2002: 57–76), the concept of rights can be divided into two main categories in terms of their characteristic features: one of which is relative rights and the other absolute rights.

Absolute rights can be asserted against anyone, regardless of kinship, legal connection, etc. The holder of that right can use it as he wishes and has the sole authority to prevent others from using it without his permission. (Öztan, B., 2002: 70) Absolute rights are divided into two categories as to their subject matter. “Personal rights” and “property rights”. Property rights are also divided into two categories: absolute rights over tangible and intangible goods or assets.

The intellectual property rights, which are one of the absolute rights (property rights) acquired over intangible goods or assets, are evaluated within this framework.

C.2. Intellectual Property and Trademarks:

In its broadest sense, Intellectual Property refers to legal rights arising from intellectual activities in the industrial, scientific, literary, and artistic fields. (WIPO Intellectual Property Handbook: Policy, Law and Use, WIPO Publication №489 (E) — http://www.wipo.int/about-ip/en/iprm/pdf/ch1.pdf)

Paragraph viii of Article 2 of the “Convention Establishing the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO)” states that “intellectual property” shall include rights relating to

- literary, artistic, and scientific works,

- artists’ performances, phonograms, and broadcasts,

- inventions in all fields of human endeavor,

- scientific discoveries,

- designs,

- trademarks, service marks, trade names and designations,

- protection against unfair competition and all other rights arising from intellectual activity in the industrial, scientific, literary, or artistic fields.

The term ‘intellectual property’ has two different pillars, one of which is related to ‘copyrights,’ which includes not only literary, artistic, and scientific works but also performing artists, phonogram producers, and broadcasters, also referred to as neighboring rights, and the other is related to ‘industrial property,’ which includes patents, designs, trademarks, geographical indications, integrated circuit topographies, and similar elements.

The following figure can be used to illustrate the above explanations:

C.3. Definition of a Trademark:

A trademark is a name, symbol, logo design, or a combination of any or all of these, used to identify and distinguish the goods and services of one person or enterprise from another. (Burshtein, Lynn M., 2005, 62–62)

The legal framework for a trademark can be found not only in international agreements (e.g. TRIPS Agreement) but also in Turkish legislation (Industrial Property Law №6769).

Article 15 of the TRIPS Agreement (Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights) states that: “Any sign or combination of signs which serves to distinguish the goods or services of one undertaking from the goods or services of other undertakings shall be recognized as a trademark. Such signs, in particular words, including personal names, letters, numerals, figurative elements and color combinations, and any combination of such signs may be registered as trademarks.”

Article 4 of Regulation (EU) 2017/1001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 June 2017 on trademarks of the European Union reads as follows “An EU trademark may consist of any sign, in particular words, including personal names, or designs, letters, numerals, colors, the shape of the goods or the packaging of the goods, or sounds, provided that such signs are capable of

(a) distinguishing the goods or services of one undertaking from the goods or services of other undertakings and

(b) being represented in the Register of European Union trademarks (‘the Register’) in such a way as to enable the competent authorities and the public to identify clearly and unambiguously the subject matter of the protection afforded to the proprietor.”

The Industrial Property Law №6769 also defines the framework of the trademark in Turkey. Accordingly, the first paragraph of Article 4 of Law №6769 reads as follows: “A trademark may consist of all kinds of signs such as words, shapes, colors, letters, numbers, sounds, the form or packaging of goods, including personal names, provided that they enable the goods or services of one undertaking to be distinguished from the goods or services of other undertakings and that they are shown in the register in a manner that clearly and precisely determines the subject matter of the protection provided to the owner.”

In view of the aforementioned definitions, it can be said that the essence of any modern trademark, regardless of its shape, composition, etc., is the “sign,” which usually has two main characteristics: “distinctiveness” and “non-deceptiveness.”

D. Conclusion:

Many factors have been at play in the making of the modern world over the last two or three hundred years, but changes in technology stand at the center of all accounts, notably the Industrial Revolution which shifted away from traditional agriculture and trade to the mechanization of production, the elaboration of the factory system, and the development of global market systems to industrial production (Mokyr, J., 1990, p.277). Scientific revolutions carried out within this context overturned not only the reigning theories but also carried with them significant consequences outside their respective scientific disciplines (Andersen, 2001, p.29).

The most important change and development affecting trademark law is undoubtedly the intensive use of the Internet. The information and communication technologies that emerged as a result of the developments in the field of science and technology, especially after the 1990s, have changed the cultural and social structure of societies and the nature of widely practiced commercial relations. The Internet, which is one of the information and communication technologies, allows global access to information in a fast and cheap way, which leads to the change in trade methods and the acceptance of the Internet as the most important marketing tool for everyone engaged in trade all over the world. The worldwide use and proliferation of the Internet have made a simple regulatory issue more complex, a phenomenon that also occurs in trademark matters where global legal protection is not available.

Needless to say, these developments have shaped and formed the current structure of modern trademarks and the relevant legal regulations, but it would be unfair to claim that the origin of the trademark should be traced back to these events.

As expressed, the core component of a trademark is the sign itself, and the stated sign is, at first hand, used to distinguish the goods and services of one undertaking from another. In order for this feature to be realized, it is considered that the sign in question must be used during commercial transactions. Therefore, a minimum commercial convenience must be present for a sign to be accepted as a trademark.

In some archaeological excavations, artifacts (oil lamps) with the ‘Fortis’ mark have been found dating back to the first three centuries of the Roman Empire. Oil lamps bearing this mark are scattered throughout the territory of present-day England, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Spain. These indicate that the mark may have been used in a manner closer to modern trademark practice. (Winterfeldt, B.J., 2002)

Therefore, it can be said that modern trademarks neither emerged suddenly in the wake of the scientific revolution, nor do they date back to 5,000 years BC, but rather were influenced in some way by the signs, signatures, etc. used in the first centuries of the Roman Empire, and it was these historical signs and marks that paved the way for modern trademarks and their current status.

References:

Books:

- FOSTER, Frank H. — SHOOK, Robert L., (1993), Patents, Copyrights & Trademarks, U.S.A, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Ord.Prof.Dr.HİRŞ, E., (1948), Fikri ve Sınai Haklar, Ankara, Ankara Basımevi

- Prof.Dr. KILIÇOĞLU, Ahmet M., (2004), Borçlar Hukuku — Genel Hükümler, 2nd Edition, Ankara

- Prof.Dr.ÖZTAN, Bilge, (2002), Medeni Hukukun Temel Kavramları, 9th Edition, Ankara

- WIPO Intellectual Property Handbook: Policy, Law and Use, WIPO Publication №489 (E) — http://www.wipo.int/about-ip/en/iprm/pdf/ch1.pdf (accessed on September 21, 2018)

- RUDOFSKY, Bernard, (1952), Notes on Early Trademarks and Related Matters, Seven Designers Look at Trademark Design, Chicago, Paul Theobald Publisher

- SHILLING, Dana, (2002), Essentials of Trademarks and Unfair Competition, New York, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Prof.Dr.TEKİNALP, Ünal, (2002), Fikri Mülkiyet Hukuku, İstanbul, Beta Basım Yayım Dağıtım A.Ş.

Articles:

- Andersen, Hane, (2001), On Kuhn, Wadsworth/Thomson, USA

- Burshtein, Lynn M., Would A Band By Any Other Name Sound Just As Sweet?, Canadian Musician; May/Jun2005, Vol. 27 Issue 3, p62–62, 1p, 1bw

- Johnson, David, (2005), Trademarks — A history of a billion-dollar business, Information Please® Database, Pearson Education

- Mokyr, Joel, The Lever of Riches, Technological Creativity and Economic Progress, Oxford, Oxford University Press: 31–57

- Winterfeldt, Brian J., Historical Trademarks: in Use since . . . 4,000 B.C., INTA Bulletin Archive: March 2002

Prepared by

N.Berkay KIRCI

Attorney at Law

Trademark & Patent Attorney

Copyright Expert