Malicious Trademarks in Turkish Legal System: The Villains of Trademark Law

---------------

This article was published online in the Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice on 01 December 2021.

For the original publication, please visit this link: https://doi.org/10.1093/jiplp/jpab133

In case you wish to cite, please cite as follows or visit the same link to cite in other formats:

N Berkay Kirci, Malicious trade marks in the Turkish legal system: the villains of trade mark law, Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice, Volume 16, Issue 11, November 2021, Pages 1273–1282, https://doi.org/10.1093/jiplp/jpab133

---------------

Abstract:

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has had irreversible effects on our lives, has also brought along a drastic change in consumer behaviors. Although there are many other underlying reasons, the pandemic and the increased use and preference of e-commerce sites are believed to have caused illicit trade to increase significantly in Turkey. A very recent report that supports this statement and was drawn up in collaboration with the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) sets out that Turkey ranks third among provenance economies for counterfeit and pirated goods.

This recent data also proves that emphasis needs to be placed on malicious trademarks in Turkey, which in this paper are referred to as the villains of trademark law and illicit trade.

In this respect, this paper will provide a definition of, and an overview of regulations on malicious trademarks in Turkish Law, along with an elaboration of criteria accepted by the Turkish Court of Cassation for the existence of a malicious trademark, considering the previous and up-to-date decisions. In addition, the legal regulations currently in force regarding malicious trademarks in Turkey and especially the stance of the Turkish courts of the first instance will be analyzed with a critical approach. Thus, we will try to signify how problematic the malicious trademark applications and registrations in Turkey are and that, unfortunately, the extent of malicious trademark usage is worse than predicted.

Keywords: Malicious Trademark Registration, Trademark, Bad Faith, Trademark Invalidation.

I. Introduction:

There is scarcely a movie script where the main character, the protagonist, does not have an enemy, the antagonist. Remember the movie ‘The Karate Kid’ (1984), the main character ‘Daniel-san’ and his opponent’s instructor: “Cobra Kai Sensei”? Try to refresh your memory and remember the final scene where the antagonist “Cobra Kai Sensei” firmly tells his student (the opponent) to ‘sweep his leg’, and our main character Daniel-san wins the contest with one broken leg. And also, do you remember the ‘Harry Potter’ (2005 – 2011) movie and the scene where ‘Lord Voldemort’ (referred to as ‘He-Who-Must-Not-Be-Named’ in the movie), representing the master of old black magic, gives in to the evil and tries to kill Harry Potter?

‘The more successful the villain, the more successful the picture.’ asserted Sir Alfred Joseph Hitchcock (13 August 1899 – 29 April 1980), an English film director, producer, and screenwriter. (1) Yet this statement does not apply to, nor is accurate for, intellectual property protection because a consistent, stable, and reliable trade environment requires predominant and sustainable intellectual property protection and enforcement.

Until the enactment of the current legislation, malicious trademarks were neither regulated as an absolute/relative ground for refusal in trademark registration nor a ground for trademark invalidation in Turkey. As will be elaborated in further detail below, Article 35 of the abolished Turkish Decree-Law No. 556 on Protection of Trademarks regulated malicious trademark applications as a separate ground for opposition in addition to absolute and relative grounds for refusal. This used to cause hesitations as to whether bad faith allegations could also be asserted as a separate ground in trademark invalidation lawsuits. To solve this specific issue and other related problems experienced in the period of the now-abolished Decree-Law and to conform with the relevant EU Directives, Regulations, and related international agreements, a new legislation (namely, Turkish Industrial Property Law No. 6769) regulating the matters of trademark, design, patent, utility model, and other industrial property issues, was put into force in Turkey as of January 10, 2017.

The first human cases of COVID-19, a disease caused by the novel coronavirus subsequently named SARS-CoV-2, were first reported by officials in Wuhan City, China, in December 2019. (2) Ever since the COVID-19 pandemic has had irreversible effects on our lives. Despite the increase in efforts to vaccinate people against COVID-19, there are still many people who are righteously hesitant to get into crowds, try to maintain their social distance, and wear masks. This tendency in consumer behavior has drastically changed commercial relations and increased the usage of e-commerce sites in Turkey. Thanks to software and applications used in the online retail industry, shopping through these channels has become so simple and easy that all transactions can now be completed in a matter of minutes. Product providers and companies can open virtual stores and reach potential customers as easily as it is for a consumer to become a member of an e-commerce site and shop there.

Although there are many other underlying reasons, the pandemic and the increased use and preference of e-commerce sites are believed to have caused illicit trade to increase significantly in Turkey. A recent report titled 'Global Trade in Fakes - A Worrying Threat' that supports this statement and was drawn up in collaboration with the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) sets out that the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated illicit trade, and further, that Turkey ranks third among provenance economies for counterfeit and pirated goods. (3)

One of the crucial conclusions drawn for Turkey in that report is that the Turkish Industrial Property Law No. 6769, which was part of the efforts for Turkey's accession to the EU and updated relatively recently with an attempt to harmonize with international standards, was not efficiently implemented and needed to be put into practice and enforced as initially envisaged.

Though not mentioned in the stated report -probably because of the difficulty in obtaining quantitative results- it is necessary to incorporate malicious trademarks into the scope of illicit trade. Hence, it would not be an exaggeration to assert that malicious trademarks are the villains of trademark law, and emphasis, needs to be given to this specific issue.

In this respect, this paper will provide a definition of, and an overview of regulations on malicious trademarks in Turkish Law, along with an elaboration of criteria accepted by the Turkish Court of Cassation for the existence of a malicious trademark, considering the previous and up-to-date decisions. In addition, the legal regulations currently in force regarding malicious trademarks in Turkey and especially the stance of the Turkish courts of first instance will be analyzed with a critical approach. Thus, we will try to signify how problematic the malicious trademark applications and registrations in Turkey are and that, unfortunately, the extent of malicious trademark usage is worse than predicted.

II. The definition of malicious trademark:

Turkish Industrial Property Law No. 6769 does not provide a clear definition of the malicious trademark. Article 6 Paragraph 9 of the same Law states that: “Trademark applications filed in bad faith shall be refused upon opposition.” In the literature, the definition of a malicious trademark has been made by taking different aspects into account. While some authors focus on the intention of the trademark proprietor (4), some argue that the evaluation should be made with a broader perspective (5), whereas others prefer to make a definition that combines these two approaches (6).

In its decision RG 512, the Joint Civil Divisions of the Turkish Court of Cassation defined malicious trademark as follows: any application or registration that takes unfair advantage of someone else's trademark by using trademark protection against its purpose, or making a backup without using it, brand trading, or blackmailing (7).

Malicious intent may exist at the very first stage of a trademark application or may occur at any time thereafter. Hence, with a perspective comprising not only the registration of a trademark but also the subsequent use thereof, it would be more suitable to assert that ‘A malicious trademark arises when the right on a sign/trademark is used to achieve an unfair purpose by exceeding the authority granted by law.’ (8)

III. Regulations on malicious trademark in Turkish Law:

In the process of Turkey’s accession to the European Union and to become a party to the Customs Union Agreement (9), many Decree Laws on intellectual property were put into force in 1995. Before the Turkish Industrial Property Law came into force in 2017, the fundamental legislation on trademarks in Turkey was Decree-Law No. 556 on the Protection of Trademarks.

The repealed Decree-Law did not regard malicious trademarks among the absolute or relative grounds for refusal in trademark registration but only as a separate ground for refusal if and to the extent an objection was raised against the publication of a trademark, as stipulated in Article 35. (10) Likewise, even though the absolute and relative grounds for refusal envisaged as grounds for objection were additionally defined as grounds for trademark invalidation in Article 42 of the Decree-Law, malicious trademarks were not regulated as grounds for trademark invalidation. (11) In the literature, this situation was seen as the most crucial reason for the emergence of ambiguities and the failure to combat malicious trademark registrations effectively in Turkish trademark law. (12)

The 11th Civil Chamber of the Turkish Court of Cassation, on the other hand, until its ANTEO decision (13), considered malicious trademark registrations not as a primary ground or basis for trademark invalidation, but as a subsidiary ground that helped to prove the main allegations (14), whereas following that decision, it can be observed that the 11th Civil Chamber of Turkish Court of Cassation consistently started to render invalidation decisions in cases where the dispute involved the registration of a malicious trademark.

The ambiguities and deficiencies in terms of malicious trademarks were also seen in other areas of trademark law. The most important and accurate criticism brought to Turkish trademark law was that the right to trademark was protected as part of property rights under Article 35 of the Constitution of the Republic of Turkey (Constitution of 1982) and, therefore, the regulations that abolish and/or limit the rights on trademark must be made by the enactment of laws, not decree-laws. (15) In fact, in the following periods, the Turkish Constitutional Court annulled some provisions of Decree-Law No. 556 for other reasons, notably, the reason mentioned above. (16)

To solve this specific issue and other related problems experienced in the period of the now abolished Decree-Law and to conform with the relevant EU Directives, Regulations, and related international agreements, Turkish Industrial Property Law No. 6769 was put into force in Turkey as of January 10, 2017. With this new legislation, malicious trademark registration is now regulated among the relative grounds for refusal in trademark registration as stipulated in paragraph 9 of Article 6 (Article 6/9). Similarly, by the enactment of paragraph one of Article 25 of Law No. 6769 stating that the absolute and relative grounds for refusal shall be regarded among the grounds for trademark invalidation, the deficiency seen in the period of Decree-Law No. 556 has been eliminated.

In other words, with the enactment of Turkish Industrial Property Law No 6769, malicious trademark registrations have not only become a relative ground for refusal in trademark registration but also a ground for trademark invalidation.

IV. Malicious trademarks in Turkish Law practice:

In the literature, malicious trademarks are classified in parallel with the regulations in German Law. The different types of malicious trademarks defined in this sense include prevention marks, pitfall marks, speculation marks, transfer marks, agent marks, defense marks, reserve marks, repetition marks, and misuse of vanity numbers as trademarks. (17)

According to the general principle arranged in the Turkish Procedural Law No. 6100, as is also stated in almost all decisions of the Turkish Court of Cassation (18) and even the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU)(19), each case must be evaluated within its circumstances on a case-by-case basis. Thus, addressing each case concurrently with its objective and subjective aspects rather than limiting malicious trademarks by classification is believed to be more adequate. During the evaluation, ‘account may also be taken of the commercial logic underlying the filing of the application for registration of the sign and the chronology of events leading to that filing.’ (20) However, it should be borne in mind that taking a subjective aspect such as intent as a basis can cause problems during the examination process and that bad faith should be determined based on objective criteria to the extent possible. (21)

Within the context of precedents heard before the Turkish Court of Cassation, the criteria accepted for the existence of a malicious trademark are the awareness of the trademark owing to a previous commercial relation or other reasons, the distinctive and well-known character of the sign, and acts that are contrary to the principles regulated in the Turkish Civil Code, Turkish Commercial Code, and Turkish Industrial Property Law.

A. The awareness of the trademark:

In cases where a trademark and its proprietor are known to the defendant on grounds of a previous commercial relation or other similar reasons, the trademark application/registration or usage in question might be regarded as malicious. A typical example of this condition in Turkey is cases where a commercial agent gets a trademark registered beyond the genuine trademark owners’ knowledge, at a time when the representation relationship between them is still ongoing or has ceased to exist. (22)

In the ‘GRİN NİCCİ’ case, the 11th Civil Chamber of the Turkish Court of Cassation stated that:

registration of a confusingly similar trademark in the defendant's name after the defendant’s authorization to sell in Turkey Grin Nicci products, imported from Korea, was abolished, was contrary to the rule of acting in good faith and fair dealing as stipulated under Article 2 of the Turkish Civil Code. (23)

In a relatively recent decision of reversal, the 11th Civil Chamber of the Turkish Court of Cassation concluded that:

since the defendant, whose distributorship contract was terminated, registered the trademark without the permission and consent of the genuine owner, with the intention to prevent the right holder from registering the trademark in Turkey and signing another distributorship agreement to get the same product marketed by other parties, the trademark registration is to be considered malicious and, therefore, needs to be invalidated. (24)

In its very recent ALİBİ decision, the 11th Civil Chamber of the Turkish Court of Cassation concluded that:

the trademark in question was created by more than one person, and while it was well within the possibility to register the sign as a multi-owned trademark, acting on the contrary and registering it in the name of one person alone is proof enough for the existence of a malicious act. (25)

Limiting the awareness of a trademark only to the existence of a previous commercial relationship would be a false assertion. In accordance with the definition of malicious trademark stated in most decisions of the Turkish Court of Cassation, making a trademark backup, brand trading, or blackmailing all predicate on the awareness factor as an essential condition. In other words, the inducement in all these situations is that the party acting contrary to the rules of honesty and abusing a trademark right is aware of the trademark and its proprietor. To put it more clearly, the party acting in bad faith when registering or using a trademark aims at obtaining an unfair advantage and thereby injures the rights of the genuine trademark owner.

With regard to malicious trademark registration/usage, the intention in doing so, and the awareness factor, the Turkish Court of Cassation in CITY’S NİŞANTAŞI case stated that:

the fact that the defendant offered to sell the internet domain names citynisantasi.com and citynisantasi.net by an email sent to the claimant and taking into consideration that further the claimant is the proprietor of a shopping mall in Nişantaşı/Istanbul and that the claimant made public statements and explanations that the shopping mall would be opened under this particular name proves that the defendant was acting in bad faith and, hence, it was decided to invalidate the trademark registration. (26)

In addition to the foregoing, registering a similar version of a trademark while another lawsuit is still in process (either pending or finalized) is also regarded as a malicious attempt.

For instance, the 11th Civil Chamber of the Turkish Court of Cassation in its ALM, ALMAN HASTANELER GRUBU, ALMAN MEDİRESİDENCE case, concluded that:

the fact that the trademark applications in question were filed with the Turkish Patent and Trademark Office (TURKPATENT) at a time when an invalidation lawsuit was still pending for the trademarks ALMAN and ALMAN HASTANESİ signifies that the applications were made in bad faith. (27)

Similarly, in the 1983ORJİNALASTROMİX case, the Turkish Court of Cassation stated that:

the defendant’s previous trademark registration for Asturomix orjinal 1983 was invalidated due to the genuine right ownership and on grounds of maliciousness. Registration of a confusingly similar trademark despite these facts and events is obviously an act of bad faith. (28)

Decisions of the TURKPATENT (29) – Reexamination and Evaluation Board (30) regarding the OCB BROWN (31) and OCB (32) trademark applications and other similar applications also show that the Office has been taking the awareness factor as a component of the criteria applied to determine maliciousness. In both mentioned decisions, it is stated that:

considering the existence of the applicant's other applications comprising the words OCB orange, OCB black, OCB green, OCB blue, OCB beige, and OCB white, there is obviously a strong similarity in terms of the sign’s word and color elements, the applicant is systematically trying to apply for trademarks that are already registered with WIPO and EUIPO on behalf of the opponent,

the trademark applications bear a high level of resemblance to the opposing party's trademark used in online sales and considering that the filing of an application for the same or similar goods/services cannot be regarded as mere coincidence, it is concluded that the registration of these applications will bring along the possibility of unfair advantage, meaning that the applications were filed in bad faith and hence need to be dismissed.

B. The distinctive/well-known character of the trademark:

In case of an attempt to register a highly distinctive sign/well-known trademark, the trademark application/registration or usage in question might be regarded as malicious.

In its U-BOAT ratification decision, the Turkish Court of Cassation decided as follows:

in the face of the fact that the sign in question is enjoying a high level of distinctiveness in the jewelry and watch sector, coupled with the absence of any convincing explanation as to why the defendant chose and registered this particular trademark, the Court found that the choice and registration of this sign by chance did not fit the ordinary course of life and hence it has decided that the defendant was acting in bad faith. (33)

The Turkish Court of Cassation in its CeBIT decision stated that:

in the existence of a well-known trademark, the presumption of possible malicious trademark registration shall prevail. (34)

Although the well-known trademark provides ease of proof due to the accepted presumption of bad faith, as emphasized in the HERCULES (35) decision of the Turkish Court of Cassation, being a well-known trademark alone is not sufficient evidence and bad faith needs to be proven.

Another case where maliciousness shall be accepted is in cases where a trademark, which is not well-known, is registered for the sole purpose of unfair use and without any reasonable explanation. (36)

C. Acts contrary to general principles regulated in the Turkish Commercial Code:

Clause 18/2 of the Turkish Commercial Code No. 6102 includes the terms of a prudent businessman and prudent merchant. The obligation to act as a prudent merchant emphasizes the necessity of showing due care expected from a cautious and foresighted merchant operating in the same line of business, but not the care expected from him according to his abilities and possibilities in his activities related to his business. (37) Trademark application/registration and usage contrary to this principle might be regarded as malicious.

The Court of Cassation in the ONLY decision, stated that:

the defendant must follow the developments in the world regarding his business which is an essential requirement of being a prudent merchant in accordance with Article 18/2 of the Turkish Commercial Code; accordingly, it is not possible for the defendant working in the same field with the claimant to claim that he did not know that the trademark in question had been registered in many countries by the claimant and that the claimant had stores opened in various countries worldwide, and thus, it has to be concluded that these defenses are contrary to the rule of acting in good faith and fair dealing as stipulated under second Article of the Turkish Civil Code, as a result of which it has to be decided that the trademark was registered in bad faith. (38)

D. Acts contrary to the general principles regulated in Turkish Industrial Property Law:

According to Turkish Industrial Property Law, the exclusive rights on a trademark are, as a rule, obtained by registration. One of the fundamental exceptions to this general rule is the principle of genuine right ownership. (39)

According to paragraph 3 of article 6 of Law No. 6769, if a right on a non-registered trademark or another sign used in the course of trade was acquired prior to the date of application or the date of the priority claimed when filing an application for the registration of a trademark in Turkey, the trademark application shall be refused upon the opposition of the proprietor of that prior sign.

As established by the decisions of the 11th Civil Chamber of the Turkish Court of Cassation (40), the prior rights on a trademark, which is one of the three important principles regarding the acquisition and protection of trademark rights, belongs to the person who created and uses that sign, who is referred to as the genuine right owner. According to Turkish Court of Cassation decisions, in such cases, the registration of the trademark only has an explanatory effect. In other words, the right to the trademark has occurred before registration. However, registration/application by a person, who has just chosen and registered a trademark without creating or using it, has a constitutive effect. Such registration/application may only grant the beneficiary a contingent right initially. Until the genuine right owner objects/sues and registers the trademark in question, ownership of the founding effect shall continue since the genuine right proprietorship on a trademark does not entitle to a second independent and individual ownership. (41)

In this respect, trademark applications/registrations or trademark usages that are contrary to these principles might be regarded as malicious.

The Turkish Court of Cassation in the NOD32 decision stated that:

the claimant has started to use the trademark NOD32 in computer software in Turkey starting from 2003, i.e., before the application date of the trademark in question, and, by way of this usage, the trademark has become well-known in its field, as a result of which the acts of the defendant, who registered the same trademark in the same classes and in the same line of business, must be regarded malicious and it has to be decided to invalidate the trademark registration. (42)

V. A Critical Approach to the Current Legal Regulations and Practices Regarding Malicious Trademarks

A. Criticism related to the current legal regulations regarding malicious trademarks:

Becoming a successful trademark is never as easy as it looks. In addition to many other factors, trademark owners must be authentic, create value, and stand out from competitors with qualified products and services to become discernable among rivals. Exceptions aside, unfortunately, with the everchanging economic, social, and cultural dynamics in Turkey, these virtues have never been widely accepted and preferred. Instead, it has always been more attractive to take improper advantage of a trademark’s endeavor, time, and investments.

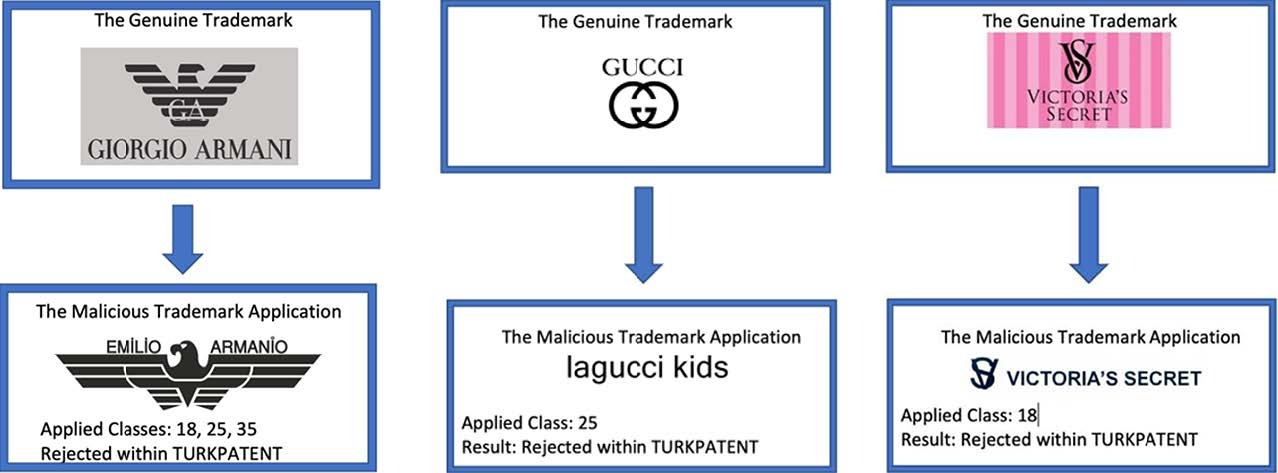

Figure 1 shows a typical example of applications observed in the trademark registry. In this type of malicious trademark application, the well-known trademark is either positioned as one of the main components of the application, or the exact same trademark is tried to be registered in a different class.

Figure 1. The typical malicious trademark applications filed within the trademark registry (43)

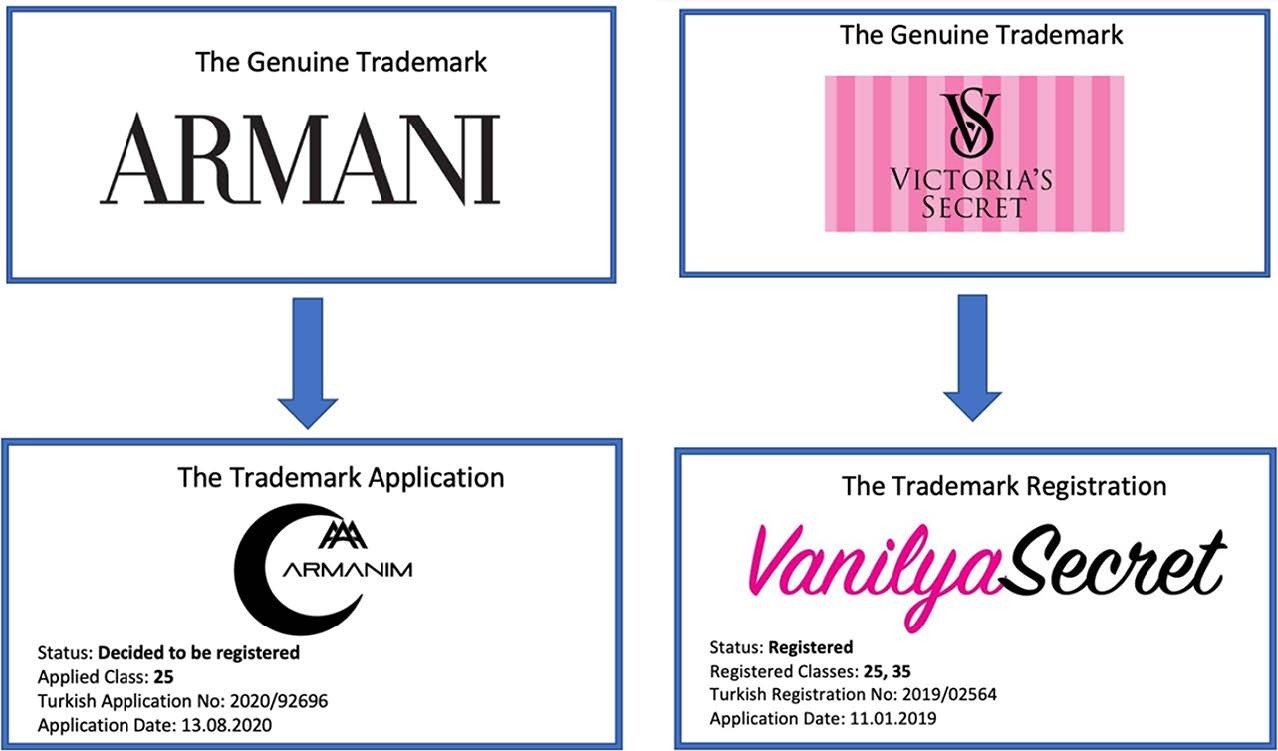

Figure 2 demonstrates that unless there is an opposition lodged against the publication of a trademark application, it may be registered since it is not possible for the TURKPATENT to reject a trademark application spontaneously during an Ex-Officio examination, based on a reason not regulated within the scope of absolute grounds for refusal.

Figure 2. Examples of trademarks registered/decided to be registered with TURKPATENT

Therefore, the first criticism regarding malicious trademarks is aimed at the existing legal regulations in Turkey.

The Legislator, being aware of the impossibility of making a regulation that would comprise all kinds of relations between persons, has laid down Article 2 of the Turkish Civil Code, which sets forth the general principles for the exercise of rights and prohibits the abuse thereof as a general limitation. (44) According to the first paragraph of Article 2 of the Turkish Civil Code (Article 2/1): ‘Everyone has to abide by the rules of honesty when exercising their rights and in fulfilling their debts.’ Similarly, the second paragraph of Article 2 of the Turkish Civil Code (Article 2/2) states that ‘the explicit abuse of any right shall not be preserved by the legal order.’ These general principles are being applied in different areas of law, including but without limitation to Trademark Law.

Indisputably, any malicious trademark registration or use of a malicious trademark will involve a violation of the rule of acting in good faith and fair dealing principles as determined in the Turkish Civil Code. In such cases, the rule/principle set up for all members of the society would be violated, which also means that the public interest is likely to be damaged.

As stated previously, malicious trademarks are regulated as a relative ground for refusal in Turkish legislation. Therefore, to prevent the registration of malicious trademark applications, it is required that an opposition is filed with TURKPATENT. In cases such as reluctance, missing the deadline, or not being aware of the publication, the process may result in trademark registration. This will not only affect the rights of the genuine trademark owner but will also cause the encouragement of malicious intent and thereby intensify illicit trade in Turkey.

Thus, it would be more appropriate to regard malicious trademarks as the absolute grounds for refusal in trademark registration, as is the case in the European Union acquis (45), which serves as a reference for Turkish Industrial Property Law. (46)

B. Criticism related to the current legal practices regarding malicious trademarks:

The criteria pointed out in this paper are crucial in terms of showing that bad faith may be in question both in the trademark application and in the post-registration phase. However, except in obvious cases, it is difficult to prove malicious intent at each stage.

In the literature, it is argued that in a legal system where property rights are essential, the regulations that abolish a substantial right should be considered exceptional, and thus it is necessary to be more careful in bringing limitations to the trademark right, which falls into the scope of property rights. (47)

Both probably due to the difficulty of proving bad faith and the justifications in the literature regarding the limitation of property rights, it is observed that the courts act very cautiously when rendering decisions about malicious trademarks.

According to very recent news of July 2021, Ankara 2nd Civil Court of Intellectual and Industrial Property Rights approved the registration decision of a trademark application of the same class comprising a bull figure, which is one of the essential elements of the well-known trademark REDBULL. (48) The mentioned trademark images are shown in Figure 3. Although the details are not known since the justified decision has not been put into writing yet, from the news, it can be assumed that according to the court's perception, when a shape, which is an essential element of a well-known trademark, is comprised in another trademark in the same class, there will be no likelihood of confusion, nor does this behavior necessarily have to be malicious.

Figure 3. Images (49) of signs subject to the court decision:

In the ACEMİ ANNELER (50) case, which is currently pending and is about trademark infringement, the claimant requested an interim injunction to prevent the use of the trademark. One of the most important defenses regarding the interim injunction was that the plaintiff had not used the trademark in the TV series, the trademark registration in question was an act of bad faith and, therefore an invalidation lawsuit had been filed, and more importantly, that the plaintiff had admitted these claims in the invalidation lawsuit, and that therefore the verdict of the invalidation case needed to be awaited.

In its hearing for an interim injunction, the court rendered its decision without considering the defenses, and therefore an appeal was filed against the decision. The 20th Civil Chamber of Ankara Regional Court of Justice examined the request for appeal, as a result of which it annulled the decision and decided to reject the request for an interim injunction. (51) Although the reversal of the interim injunction decision took a relatively short time, this did not prevent the related TV series from being taken off the air.

As can be seen, the excessively cautious approach of the Turkish courts of first instance to the issue of bad faith often causes crucial irreversible loss of rights, encouraging people with malicious intent, and, consequently, ends up with an increase in illicit trade, as is manifested in the report mentioned in the introduction of this paper.

In this sense, it is considered that especially the courts of first instance, when examining the issue of bad faith, should adopt a strict stance when analyzing each dispute and comply with the criteria given by the Turkish Court of Cassation and even CJEU in detail. These precautions will eventually prevent the loss of rights and will be very beneficial in the combat against illicit trade and malicious trademarks.

VI. Conclusion:

Although there are many other underlying reasons, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic and the increased use and preference of e-commerce sites are believed to have caused illicit trade to increase significantly in Turkey. The report titled 'Global Trade in Fakes - A Worrying Threat' drawn up in collaboration with the OECD and the EUIPO (published on June 22, 2021) also testifies these assertions. Though not mentioned in that report, it is necessary to incorporate malicious trademarks into the scope of illicit trade. Hence, it would not be an exaggeration to assert that malicious trademarks are the villains of trademark law, and emphasis, needs to be given to this specific issue.

A malicious trademark arises when the right on a sign/trademark is used to achieve an unfair purpose by exceeding the authority granted by law. Within the context of the precedents heard before the Turkish Court of Cassation, the criteria accepted for the existence of a malicious trademark can be classified as the awareness of the trademark owing to a previous commercial relation or other reasons, the distinctive and well-known character of the sign, and acts that are contrary to the principles regulated in the Turkish Civil Code, Turkish Commercial Code, and Turkish Industrial Property Law.

Malicious trademarks are regulated as a relative ground for refusal in Turkish legislation, which makes it impossible for the TURKPATENT to reject a malicious trademark application spontaneously during the Ex-Officio examination. This means that in order to prevent the registration of malicious trademark applications, it is required that an opposition is filed with TURKPATENT. In cases such as reluctance, missing the deadline or not being aware of the publication, the process may result in trademark registration.

Any malicious trademark registration or use of a malicious trademark will involve a violation of the general principles as determined in the Turkish Civil Code. Any such case will violate the rules/principles established for and applicable to all members of the society, which also implies a likelihood of causing harm to the public interest. Thus, it would be more appropriate to regard malicious trademarks as the absolute grounds for refusal in trademark registration, as is the case in the European Union acquis, which serves as a reference for Turkish Industrial Property Law.